On Mind, Language and Machines.

I often find myself pondering on the incredible tool that evolution has gifted to the human species. In this essay, I will talk about many topics I find interesting in the past and future evolution of language and the intricate and incredible connections that biological processes yield with technology and mathematics.

The Big Leap

What makes us different from other animals, such as intelligent mammals that are so genotypically and biologically close to us? Many may think that just an opposable thumb is what granted us the power of crafting tools, while I fall into the category of people that think that the birth of language was the big evolutionary leap between primates and humans. In their amazing essay “Why Only Us: Language and Evolution”, Noam Chomsky and Robert Berwick explain recent developments in linguistic theory and biology to offer an incredible evolutionary perspective on the arising of language. While many other animals have the ability to communicate through sound, only us humans can express infinitely complex thoughts through the use of hierarchical language. Since complex language is a self-arising and innate capacity of every human phenotype that goes through correct development, and has spanned over many thousands of years, all the continents and a huge amount of radically different languages, it is logical to be convinced that the birth of language can be isolated within an evolutionary phenomenon, somewhere in-between ape and man; though we have not yet been able to isolate and understand precisely what has been the phenomenon that unleashed this amazing thought tool. From the Berwick and Chomsky point of view, human language has first arisen as a tool for the internal understanding of what we perceive, and then has slowly become a tool for exchanging our internal understandings of the world through externalization.

Songbirds and machines

Although many other animals, not only mammals, are able to externalize signals to communicate with other individuals of their species, we have only been able to see such semantic complexity in the way humans communicate. Many animals communicate in a manner that can be interestingly represented with formal systems such as finite-state automata. While being an extremely complicated and complex process, we can express the phonetics of human languages in finite state machines, while it is thought to be impossible, due to the recursive nature of human language semantics, to represent hierarchically and recursively structured semantical thought through the use of formal systems akin to FSA. Berwick has published another interesting paper on the subject, which is also cited in the aforementioned essay, where the authors try to explain with zen-like simplicity what a hypothetical understanding of the linguistic of songbirds is like (in particular, Lonchura Striata Domestica, also known as Bengalese finch). The paper abstract is the following:

Unlike our primate cousins, many species of birds share with humans a capacity for vocal learning, a crucial factor in speech acquisition. There are striking behavioral, neural and genetic similarities between auditory-vocal learning in birds and human infants. Recently, the linguistic parallels between birdsong and spoken language have begun to be investigated. Although both birdsong and human language are hierarchically organized according to particular syntactic constraints, birdsong structure is best characterized as ‘phonological syntax’, resembling aspects of human sound structure. Crucially, birdsong lacks semantics and words. Formal language and linguistic analysis remains essential for the proper characterization of birdsong as a model system for human speech and language, and for the study of the brain and cognition evolution.

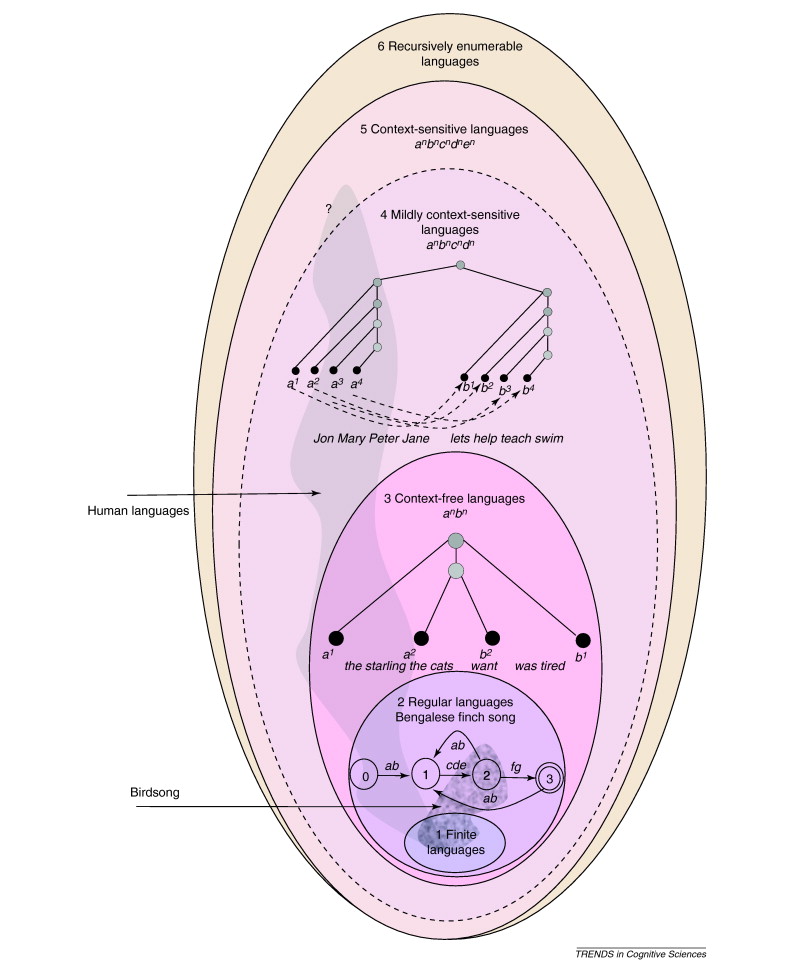

Most importantly, the paper shows that although birds exhibit some capabilities of expressing their perception (or conception?) through language, the grammars of this language fall into regular languages and not into the broader category of context-free languages, as they probably lack the ability to produce recursive sentences.

Deterministic finite state machines are an essential formal system and thought tool in many theoretical and applied Computer Science topics. Many components of processing units on chips are built with an abstraction provided by two particular kinds of finite state machines, precisely, Mealy and Moore automata. Most importantly, deterministic FSA can be used to produce regular languages. The set of context-free languages is instead a more general concept that comprises regular languages, and is identical to the set of the languages accepted by pushdown automata. Context-free languages can model natural language and are the basic ideas behind parsers and compilers that are essential components of programming languages.

Chomsky has also drawn a very interesting conceptual map of the kinds of languages that exist throughout nature.

Berwick’s paper also poses some really interesting research questions on the topic

Can birds be trained to recognize truly nested dependencies, even if just of finite depth? What are the neural mechanisms underlying variable song sequences in songbirds? Both human speech and birdsong involve sequentially arranged vocalizations. Are there similar neural mechanisms for the production and perception of such sequences in songbirds and humans? … As a result, considerable controversy remains as to whether any non-human species can truly recognize strictly context-free patterns

The cognitive tradeoff hypothesis

There is a curious hypothesis in modern neuroscience about some important differences that arose in the brain when humans diverged from primates many millions of years ago. You can watch on YouTube a very interesting and discoursive video by Michael Stevens on the topic.

It is a widely accepted fact that human ancestors may have arisen when groups of primates descended from trees and wandered off in the savanna. In a few words, what the cognitive tradeoff hypothesis tells us is that because of the radical change in the environment where our primate ancestors have lived, during the course of hundreds of millennia the section of our cerebral cortex related to short term visual memory has shrunk, leaving space to other regions of the neocortex involved in language and social abilities. Language as we know it may have been one of the strategies that kept us alive in the savanna. This hypothesis tells us that something must have been sacrificed, such as detailed short term memory, leaving space for a radical rewiring of the structure of the arcuate fasciculus, a large white matter tract of the brain that functions as a linker between two important areas.

The main role in this particular and quite niche field of research has been carried on by Professor Tetsuro Matsuzawa of Kyoto University’s Primate Research Institute, one of the world’s leading primatologists.

Prof. Matsuzawa, through his cognitive research of chimpanzee Ai over a period of nearly 30 years, is probing the evolutionary origins of the mind and behavior of humans, Homo sapiens. He is internationally renowned as the pioneer of a new research field called ‘comparative cognitive science’.

One of his most interesting works is the series of experiments carried on to test the chimpanzees’ ability to memorize the order and position of numbers on a touch screen. All of those experiments have been carried on monkeys that voluntarily engage in the “game” at any time, receiving a treat if they complete the puzzle correctly.

The results are impressive. The most impressive of all the chimpanzees studied by Matsuzawa are Ai (which means “love”) and her son Ayumu (walk). They need only an incredibly short amount of time, half a second, to memorize the location of a dozen numbers on a screen before they disappear, covered by gray boxes. The fact that their short term memory is incredibly fast may be due to the fact that in the wild, especially between tree branches, chimps need to take decisions instantly and therefore need to memorize precisely the location of the objects in their visual fields, to decide if they have to escape predators or where food and safe branches are.

Berwick and Chomsky in the essay Why Only Us, also denote that the basis for human language capabilities may reside in a stronger connection between the language comprehension area in the temporal lobe (Wernicke’s area) with the speech area in the frontal lobe (Broca’s area).

The topic has been first investigated by James K. Rilling:

The arcuate fasciculus is a white-matter fiber tract that is involved in human language. Here we compared cortical connectivity in humans, chimpanzees and macaques (Macaca mulatta) and found a prominent temporal lobe projection of the human arcuate fasciculus that is much smaller or absent in nonhuman primates. This human specialization may be relevant to the evolution of language.

The human arcuate fasciculus differed from that of the rhesus macaques and chimpanzees in having a much larger and more widespread projection to areas in the middle temporal lobe, outside of the classical Wernicke’s area. We know from previous functional imaging studies that the middle temporal lobe is involved with analyzing the meanings of words. In humans, it seems the brain not only evolved larger language regions but also a network of fibers to connect those regions, which supports humans’ superior language capabilities.

A chimpanzee with more superficial connections between these two areas may not have a system that facilitates the arising of complex verbal language. Although chimps have language, theirs is linear, simple and as songbirds, they lack the ability to express thoughts in a recursive manner. Maybe, they also lack the ability to ponder about their past and future as we do. We have to be careful in not to fall into anthropocentrism when we are comparing ourselves to animals whose genome is 98.77% identical to ours.

The Incredible and Yet Unknown Computational Power of Brains

During the last few decades, we have been able to emulate many interesting learning phenomena (that we colloquially call Artificial Intelligence or Machine Learning) by inspiring ourselves from some of the processes that happen inside of biological brains and thanks to incredible advancements in computing power, incentivized by exponential progress in computer architecture and computing parallelization.

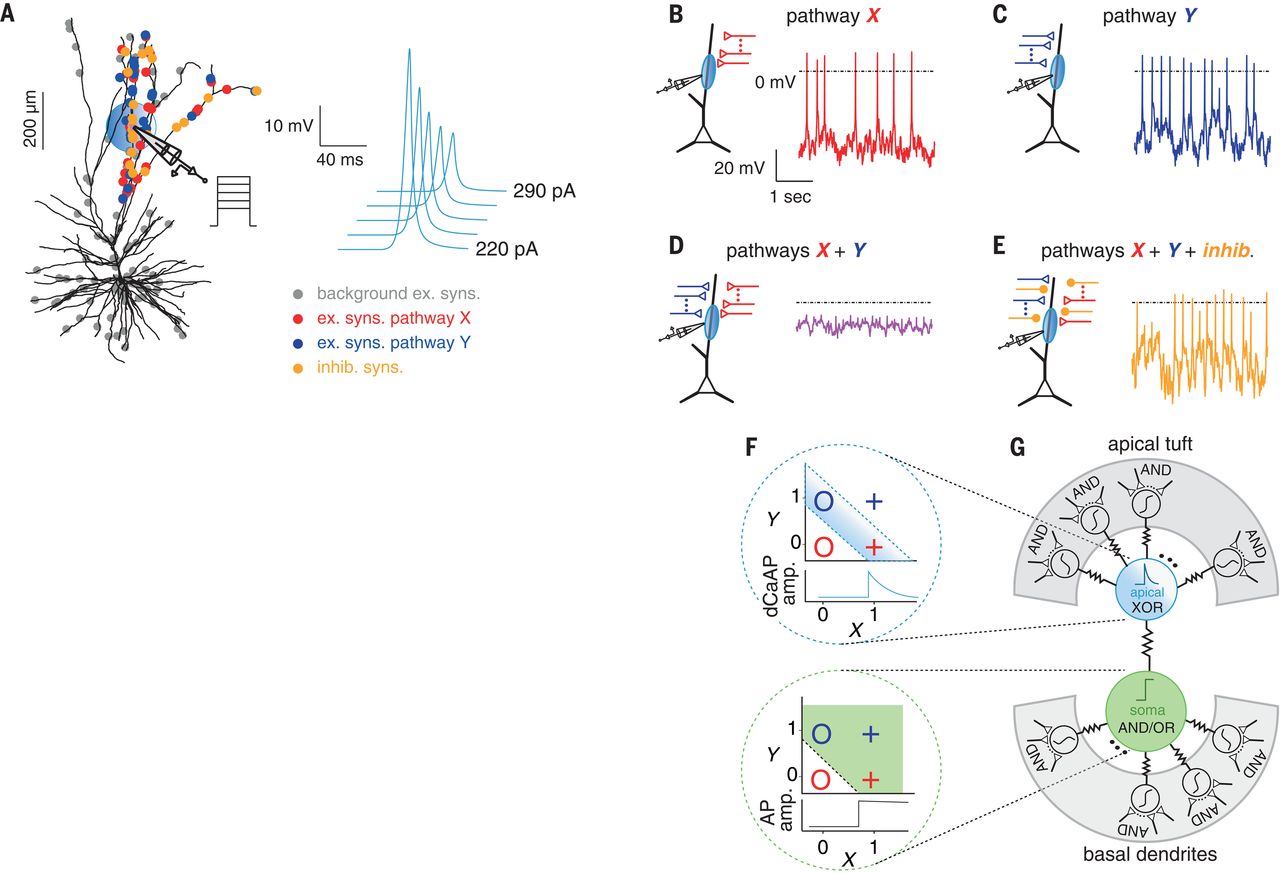

Most artificial neural networks are based on a formalized (and greatly simplified) modelization of neurons called perceptrons. We have long thought, by observing mostly mice neural tissue in vitro, that individual biological neurons could only compute, when compared to propositional logic, some particular linearly separable functions. A recent discovery tells us that our neocortical neurons can compute more of what we thought, especially, that single pyramidal neurons are able to classify linearly nonseparable inputs, which has been conventionally thought to require a whole neural network. This may tell us more about the biological differences that make our brains capable of such complex language capabilities.

Here’s an excerpt from the paper “Dendritic action potentials and computation in human layer 2/3 cortical neurons”:

It has long been assumed that the summation of excitatory synaptic inputs at the dendrite and the output at the axon can only instantiate logical operations such as AND and OR. Traditionally, the XOR operation has been thought to require a network solution. We found that the dCaAPs’ [calcium-mediated dendritic action potentials] activation function allowed them to effectively compute the XOR operation in the dendrite by suppressing the amplitude of the dCaAP when the input is above the optimal strength.

(F) (Top) Solution for XOR classification problem using the activation function of dCaAP (above the abscissa). X and Y inputs to the apical dendrites triggered dCaAPs with high amplitude for (X, Y) input pairs of (1, 0) and (0, 1), marked by blue circle and red cross, but not for (0, 0) and (1, 1), marked by red circle and blue cross. (Bottom) Solution for OR classification. Somatic AP was triggered for (X, Y) input pairs of (1, 1), (0, 1), and (1, 0), but not for (0, 0). (G) Schematic model of a L2/3 pyramidal neuron with somatic compartment (green) presented as logical AND/OR gate with activation function of somatic AP, apical dendrite compartment as logical XOR gate, and basal and tuft dendritic branches, in gray background, as logical gate AND due to the NMDA spikes.

Mapping the Connectome

Understanding more about the structure of connections between biological neurons and regions of the brain is key for future understanding about ourselves, and consequently language and more intelligent artificial systems.

From Wikipedia:

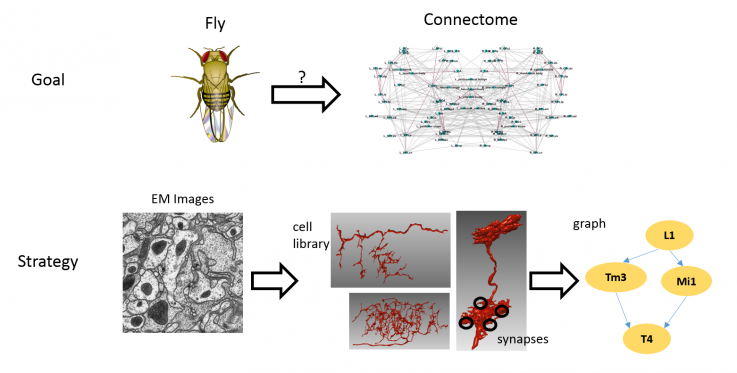

A connectome (/kəˈnɛktoʊm/) is a comprehensive map of neural connections in the brain, and may be thought of as its “wiring diagram”. More broadly, a connectome would include the mapping of all neural connections within an organism’s nervous system. The production and study of connectomes, known as connectomics, may range in scale from a detailed map of the full set of neurons and synapses within part or all of the nervous system of an organism to a macro scale description of the functional and structural connectivity between all cortical areas and subcortical structures. The term “connectome” is used primarily in scientific efforts to capture, map, and understand the organization of neural interactions within the brain.

Rendering of a group connectome based on 20 subjects. Anatomical fibers that constitute the white matter architecture of the human brain are visualized color-coded by traversing direction. Read more in this paper:

This year, precisely in January 2020, a breakthrough research article has been published by researchers at Google AI and HMMI’s Janelia Research Campus. The entire connectome of a region of a fruit fly brain (drosophila), called the “hemibrain” has been produced and studied in detail. To produce such a high-resolution connectome, they sliced the fruit fly brain into 20-micron thick slabs, and each slab was imaged by an ion beam scanning microscope at an 8x8x8 cubic nanometer resolution. Incredibly, the entire data has been released publicly and you can browse the full drosophila hemibrain connectome in your browser.

A picture displaying the overview of the FlyEM project by the Janelia Research Campus:

In neuroscience, a long-standing hypothesis is that the connectivity between brain cells plays a major role in the function of the brain. While technical difficulties have historically been a barrier for neuroscientists trying to study brain networks in detail, this is beginning to change. Last year, we announced the first nanometer-resolution automated reconstruction of an entire fruit fly brain, which focused on the individual shape of the cells. However, this accomplishment didn’t reveal information about their connectivity. … In collaboration with the FlyEM team at HHMI’s Janelia Research Campus and several other research partners, we are releasing the “hemibrain” connectome, a highly detailed map of neuronal connectivity in the fly brain, along with a suite of tools for visualization and analysis.

If this research yields significant results in understanding brains much smaller than ours, the evolution of neural connectome imaging will surely bring enormous advancement in understanding what areas of the brain specifically played a role in the arising of complex, hierarchical and recursive language in us humans. Enormous progress will be made in artificial models emulating brains. These models, as they already did in the past, will provide a lot of insight into the nature of natural language, and many interesting applications are being currently discovered.

When You Connect Conception and Perception

In the previous paragraphs, I have written about a neuroscientific view of language, brains and mind. Now, I’d like to talk more about some of the philosophical implications of language. Language is fundamental in the relationship between conception and perception. Formally,

Conception is the capacity, function, or process of forming or understanding ideas or abstractions or their symbols

Perception is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information, or the environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, which in turn result from physical or chemical stimulation of the sensory system

The key role played by language is simultaneously simple and extremely complex. It allows us to externalize what we conceive, through the use of written text or verbal conversation, it also allows us to compare what we perceive with other members of our species. Most importantly, language is a tool to internally process and understand the perception of ourselves and the universe around us. It plays a fundamental role in our individual development during infancy and the rest of our lives. It is crucial for learning because it feeds our will to look for more, giving our minds an internal explanation of the visual/auditory stimuli we perceive. This is the bridge between conception and perception. For example, how many times have you struggled to understand a complex schematic drawing until you read or were told a natural language explanation of it? How many times have you heard or read explanations of complex systems and have struggled to understand them until you had some visual schematics of the systems in front of you? Language is fundamental for a properly working imagination and the ability to pose ourselves questions is crucial for the arising of curiosity: the more complex the questions we pose to ourselves are, the more astonishing are the answers we find by looking for what we were seeking in the first place. Language helps us go through good and bad times in our lives. It helps us create and break social bonds, it helps us survive, it lets us love, by empowering us with empathy and lets us hate and reject, creating apathy. Language serves as a bridge to process and express almost everything our conscious minds enter in contact with. Let’s not forget that it also helps us individually and collectively understand the passing of time. It is truly a peculiar bridge between conception and perception: the more you try to understand it, the more it is permeated with an almost magical feeling of being full of surprises but incomplete, simple but unintelligible, recursively endless and yet so easy to tackle. Here’s one of my favorite quotes from the book Gödel, Escher, Bach by Douglas Hofstadter that perfectly encapsulates what unintelligible recursion feels like:

The trap is the idea that before you can understand any message, you have to have a message that tells you how to understand that message;

The Role of Formal Systems in Understanding Nature

Formal systems, not to be confused with formal semantics in linguistics, consist of a formal language together with a deductive apparatus. Formal languages are extremely simplified subsets of written language, whose strings are well-formed according to very restrictive sets of rules. Deductive systems may consist of a set of transformation rules (rules of inference) and a set of axioms. Mathematics, which means the study of topics as quantity, structure, space, and change, fundamentally relies on Mathematical Logic, which through formal systems, deductive reasoning and incremental manipulation of well-formed strings has become a fundamental tool for humanity to describe even more fundamental properties of the universe.

As strange as it may sound, formal languages, strict and simplified versions of natural language, helped us understand and conceive an uncountable number of phenomena we can and cannot perceive. Upon interpretation, well-formed strings belonging to formal systems can be turned into natural language statements, although a formal string may have many logically valid interpretations upon different domains, it only makes sense to give a formal system an interpretation which yields a valid isomorphism to reality, to explain things we are aware of and can perceive. It is somehow humorous how our current understanding of the complexity of the universe relies so heavily on simplification, and it is easy to see that abstraction is another fundamental power that language has gifted to us.

To discover properties of axiomatic systems, upon valid interpretation and abstraction, means to discover logically valid properties of reality. Well-formed strings derived from inference and deduction rules are called theorems. To tell if a well-formed string is actually a theorem of an axiomatic system, a process called a proof must be followed.

A formal proof or derivation is a finite sequence of well-formed formulas (which may be interpreted as sentences, or propositions) each of which is an axiom or follows from the preceding formulas in the sequence by a rule of inference.

Although fundamental to all sciences, formal axiomatic systems have inherent limitations of an almost paradoxical nature. These results are called the Gödel’s incompleteness theorems and were published by the Austrian Mathematical Logician and Analytic Philosopher Kurt Gödel in 1931. They carry a powerful intrinsic meaning that upon correct interpretation, shows that it is impossible to find a complete and consistent set of axioms for all mathematics. You can read more about Gödel’s incompleteness theorems on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Gödel’s two incompleteness theorems are among the most important results in modern logic, and have deep implications for various issues. They concern the limits of provability in formal axiomatic theories. The first incompleteness theorem states that in any consistent formal system F within which a certain amount of arithmetic can be carried out, there are statements of the language of F which can neither be proved nor disproved in F. According to the second incompleteness theorem, such a formal system cannot prove that the system itself is consistent (assuming it is indeed consistent). These results have had a great impact on the philosophy of mathematics and logic. There have been attempts to apply the results also in other areas of philosophy such as the philosophy of mind, but these attempted applications are more controversial.

But what does it mean to prove that all axiomatic systems are incomplete?

A set of axioms is (syntactically, or negation) complete if, for any statement in the axioms’ language, that statement or its negation is provable from the axioms […] there are sentences expressible in the language of first-order logic that can be neither proved nor disproved from the axioms of logic alone.

The implications are many. The incompleteness theorems show that there is a limit to provability: if formal axiomatics systems are one of the most powerful tools derived from human language, fundamental to all logic and deduction, it is chilling to think that they will always be inherently incomplete, and unable to give us a complete view of the universe. This incompleteness may not only be related to rigid mathematical systems that rely on even stricter derivation rules. As soon as one gets a grasp of Gödel’s two incompleteness theorems one can easily imagine a bidirectional map between the theorems in axiomatic system languages and the realm of natural, implicit thought and language. Still, from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Sometimes quite fantastic conclusions are drawn from Gödel’s theorems. It has been even suggested that Gödel’s theorems, if not exactly prove, at least give strong support for mysticism or the existence of God. These interpretations seem to assume one or more misunderstandings which have already been discussed above: it is either assumed that Gödel provided an absolutely unprovable sentence, or that Gödel’s theorems imply Platonism, or anti-mechanism, or both.

While Gödel tried to logically prove that a god exists, his incompleteness theorems do not really carry a religious meaning. It is a very subjective topic and it is upon the reader’s interpretation to decide if the topic of axiomatic systems yields a hidden religious substance. What is objectively frightening to think, although formal systems have proven to be a fundamental tool for understanding reality, is that even if we are living in times were scientific advancements are following an exponential growth, we are still really, really far away from understanding just a crumb of “a theory of everything”, or even the most basic question you may ask yourself when pondering on the nature of nature itself.

What is language? Sketches of random thoughts and a view of one of my favorite squares. Author illustration.

Language and Machines

Formal systems and languages are fundamental to computer science. Although they are still considered niche by the majority of people not familiar with formal science, in the last decade computing became even more ubiquitous than it has ever been. Computing is everywhere now: you are probably reading this article on your laptop or smartphone, as I’m typing on them. Chances are that if you ever bought any electrical tool in your lifespan, these tools sitting in your house are built with electronic components, axiomatic systems, and most importantly programming languages. Although formally syntactically incomplete because of the incompleteness theorems, electronic chips, processors, calculators and computers are built with a really clever constructive arrangement of formal axiomatic logic according to the latest discoveries of the laws of physics. Stop a second to ponder and think that just a single binary operation (NAND: Negated AND) from propositional calculus, where values can only be true or false, 0 or 1, is functionally complete and with just the power of abstraction, recursion and an incredible amount of human work can compute everything we can deterministically compute with a Turing Machine.

In logic, a functionally complete set of logical connectives or Boolean operators is one which can be used to express all possible truth tables by combining members of the set into a Boolean expression

But what is a Turing Machine?

A Turing machine is a mathematical model of computation that defines an abstract machine, which manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite the model’s simplicity, given any computer algorithm, a Turing machine capable of simulating that algorithm’s logic can be constructed.

Turing machines are still the main computational model used to build modern deterministic computers. Finite-state and pushdown automata can be computed by suitably built or simulated Turing machines, and therefore such machines can be used to algorithmically compute interpretations of languages produced by both regular and context-free grammars. This process can then be nested recursively in an infinite manner, creating algorithms that “understand” even more languages that can “interpret or compile” clever algorithmic descriptions of mathematical, biological, linguistic, auditory or visual processes until limits in computing power and memory are hit. Do not forget that machines have to be built by following the laws of micro and macroscopic physics.

Programming languages and machines are a very important tool to bridge conception, perception, worldwide information sharing and fundamentally, deterministic, recursive and automated methods of calculating mathematical expressions and proving statements in formal axiomatic systems. Computer languages are built upon really clever methods of connecting conception, perception (through human-machine interaction peripherals) and deductive and axiomatic reasoning. Formal systems such as Lambda Calculi or statements such as the Böhm–Jacopini theorem are noteworthy citations. Such as natural language, programming has the same sort of mystical feeling attached to the practice. Programming languages are:

Full of surprises but incomplete, simple but unintelligible, recursively endless and yet so easy to tackle

Nondeterministic and quantum computing are coherently related areas of research that are being currently explored, and coupled with computational complexity, those two topics should require to be explained in an separated essay to avoid divergence from the topic of language and mind.

It seems that because of consumerism, computational devices have lost their axiomatically logical nature as tools of thought. As digital commerce in the last two decades began revolving completely on data collection, mindless entertainment and advertisement, the scientific nature of computing machines seems like it has been long forgotten. Although human-machine interfaces are slightly more intuitive when presented visually, it seems like people not into academia or specific job sectors have long forgotten the power that language has to connect perception and conception, even when it represents algorithmic processes on machines. Slow progress is being made, by teaching principles of programming languages to adolescents and toddlers, also by teaching them that computer languages, like their natural counterparts, will be fundamental tools in their future adult lives.

The difference is subtle. As stated before in previous paragraphs, language is the fundamental tool to compare and perfect your actions and to empower curiosity and empathy. When interacting with machines, not producing valid language statements while interpreting visual and linguistic stimuli is like being struck with digital aphasia. Nowadays, people who do not know any programming language may be constantly typing their feelings on their social network profiles, (this topic requires a separate debate) but are missing the bridge that puts them in real control of the machines we hedonistically feel the need to buy.

Let’s not forget that what has allowed us to create the simultaneously beloved and hated artificial intelligence systems during the last decade, have been advancements in computing, programming languages and mathematics, all of those branches of thought derived from conscious manipulation of language. Even if they may present scary and dystopic consequences, intelligent artificial systems will very rapidly make the quality of our lives better, just as the invention of the wheel, iron tools, written language, antibiotics, factories, vehicles, airplanes and computers. As technology evolves, our conceptions of languages and their meanings should evolve with it.

Genetic Code: A Language We Do Not Own

There are many opposed scientific opinions on whether DNA and RNA, the building blocks of biological life, are languages or not. DNA or deoxyribonucleic acid is a molecule composed of two chains that coil around each other to form a double helix carrying genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses. DNA chains are composed of simpler monomeric units called nucleotides, each one of them is composed of one of four nucleobases: respectively Cytosine, Guanine, Adenine and Thymine. Nucleotides can only pair through hydrogen bonding patterns: base pairs can only be guanine-cytosine and adenine-thymine to allow DNA to maintain a regular helix structure.

While we are now sure that DNA is physical code, it is also known that DNA is radically different from any formal or natural language created by or emerged from humans. DNA involves many chemical and local construction rules that affect itself from a small, single genome-scale to full genotype scales. After this construction rules are respected, whole organisms (phenotypes) emerge from the interaction of DNA with its surrounding environment. It is possible to encode natural human language in DNA just like we can encode plain English in ASCII code, Unicode or written words; however, this correspondence is not bijective: sadly, the DNA in our cells does not yield a natural human language interpretation we can directly decipher.

We have very recently begun to partially understand what genetic code is and what it does, and whether it has a language-like nature or if it has emerged completely randomly at some point in time on an early planet Earth. We mostly know precisely when and how mathematical theories and systems have been invented because we have created them. Differently, we can only hypothesize where genetic code comes from. We know that life needs specific physical and chemical conditions to form, but the reasons for its existence or if it has been invented by superior intelligence are doubts that emerge naturally in every human individual capable of pondering at least once during its life. Computer programming and algorithmics have very recently begun their journey as tools that aid us in progressing such scientifical research. A whole branch of computer science called Bioinformatics has rapidly emerged specifically to tackle the processing of biological data (mostly genetic code) aided by computing machines.

Bioinformatics includes biological studies that use computer programming as part of their methodology, as well as a specific analysis “pipelines” that are repeatedly used, particularly in the field of genomics.

Many of the computerized operations carried by molecular biologists, biochemists and bioinformatics researchers on DNA and genetic code are algorithmically similar to many string manipulation procedures that are ubiquitous in computer science. The algorithms for computing the edit distance or difference between two pieces of computer code and DNA are essentially the same. DNA is not computer code and until we have a complete deterministic interpretation of it, some of the sequencing and manipulation algorithms have to be radically, physically and conceptually different from algorithms on mathematical computer code. Just right now, we are discovering incredible approaches for DNA and RNA editing. For example, the CRISPR-Cas system is a prokaryotic immune system that confers resistance to foreign genetic elements such as those present within plasmids and bacteriophage viruses, that can be used to edit genomic sequences in vivo.

CRISPR gene editing is a genetic engineering technique in molecular biology by which the genomes of living organisms may be modified. It is based on a simplified version of the bacterial CRISPR-Cas9 antiviral defense system. By delivering the Cas9 nuclease complexed with a synthetic guide RNA (gRNA) into a cell, the cell’s genome can be cut at the desired location, allowing existing genes to be removed and/or new ones added in vivo.

Here’s an excerpt from the breakthrough paper “Chemically modified guide RNAs enhance CRISPR-Cas genome editing in human primary cells” published in Nature Biotechnology in September 2015:

CRISPR-Cas-mediated genome editing relies on guide RNAs that direct site-specific DNA cleavage facilitated by the Cas endonuclease. Here we report that chemical alterations to synthesized single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) enhance genome editing efficiency in human primary T cells and CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Co-delivering chemically modified sgRNAs with Cas9 mRNA or protein is an efficient RNA- or ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-based delivery method for the CRISPR-Cas system, without the toxicity associated with DNA delivery. This approach is a simple and effective way to streamline the development of genome editing with the potential to accelerate a wide array of biotechnological and therapeutic applications of the CRISPR-Cas technology.

If you wish to learn more on DNA manipulation, you can read the libre text by Henry Jakubowski on this web page.

However, the search for a deterministic meaning of DNA will progress very slowly until the fundamental guiding principles are uncovered. It is quite mesmerizing to think that genetic code not only denotes the characteristics of every living being but also describes genetic information carried by non-living organisms such as viruses. Some living organisms on planet earth may feel alien and distant from us, but what really breaks all intuition are non-living organisms. By the biological definition of “life”, a virus is not alive, yet we might call it an “organism” because it has a very high degree of organization and it is made of some of the same things that living organisms are made of, such as proteins and DNA.

From Wikipedia:

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids - pieces of DNA that can move between cells - while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer, which increases genetic diversity in a way analogous to sexual reproduction.

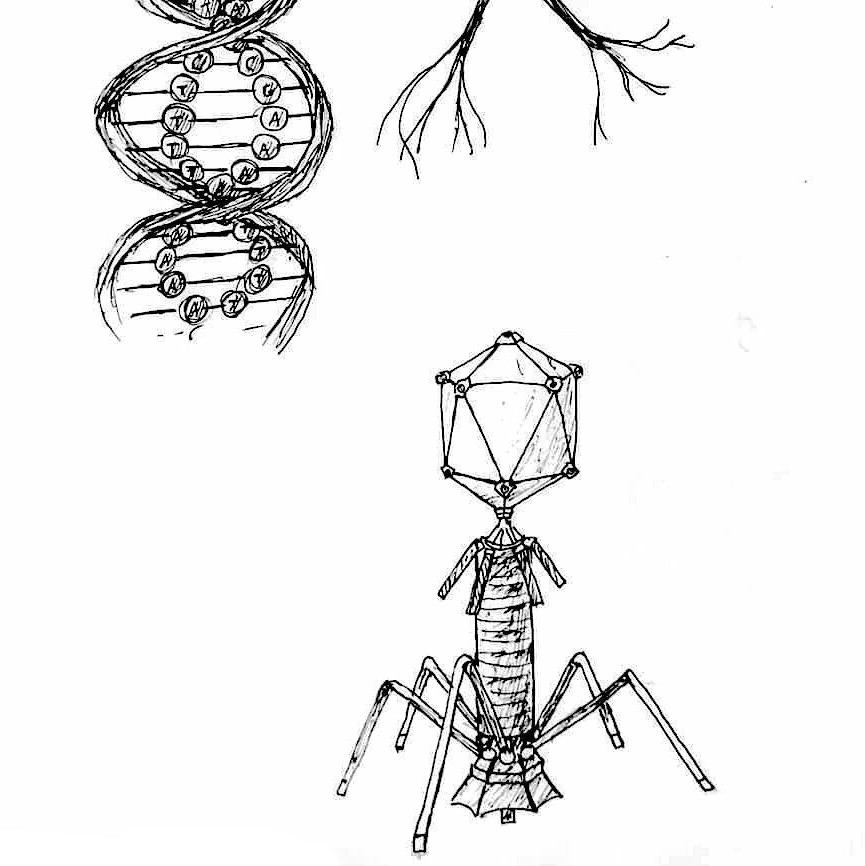

Here is the author’s illustration of a bacteriophage, a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term

was

derived from “bacteria” and the Greek φαγεῖν (phagein), meaning “to devour”. Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that

encapsulate a DNA or

RNA genome. To enter a host cell, bacteriophages attach to specific receptors on the surface of bacteria and

either destroy the bacterial cell or integrate with host DNA to reproduce.

Conclusion: The Incompatibility of Conception and Perception

The fact that we use complex and symbolic ways of exchanging messages does not mean that we are any better than any other species. We aren’t better because we can talk. It just means that the path that we took required it and although it may be the most incredible power we have received by biological evolution, it is not perfect and leaves us with one of our most great defects: doubt, uncertainty and the paradoxical incapability of expressing things that cannot be expressed.

Although we think that there is not, we do not really know if on this planet (or its few light-years surroundings) there exists some sort of organism, different from humans, living or non-living, that is capable of complex hierarchical language to express itself. If such an organism exists, its language may be astonishingly simpler, almost identical or incredibly more complex than ours.

The world is a mesmerizing pot of chaos and the gift of language not only makes us capable of analyzing through conception the environments we interact with, but it also grants us the ability to externalize what we perceive about ourselves and the rest of the world. At least to me, when something happens that blends the line between these two modes of interacting with the world, I feel a cold shiver down my spine and I feel that there may not exist a difference between what I am and what the universe is. The more we try to engrave this feeling in a verbal form, the more it loses its own essence. How can you try to express with words what words cannot express? May this eternal and inconceivable incapability of bridging perception and conception together what makes us humans ponder on the meanings of life?

Bibliography and suggested reads

This article was heavily inspired by Douglas Hofstadter’s eternal classic Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid.

- Why Only Us: Language and Evolution - Noam Chomsky and Robert Berwick - MIT Press - 2014

- Songs to syntax: the linguistics of birdsong - Robert C. Berwick. Kazuo Okanoya, Gabriel J. L. Beckers, Johan J. Bolhuis - 2011

- Neurophysiology of Birdsong Learning - R.Mooney, J.Prather, T.Roberts - Academic Press - 2008

- Dendritic action potentials and computation in human layer 2/3 cortical neurons - Albert Gidon, Timothy Adam Zolnik, Pawel Fidzinski, Felix Bolduan, Athanasia Papoutsi, Panayiota Poirazi, Martin Holtkamp, Imre Vida, Matthew Evan Larkum - Science, 2020

- Working memory of numerals in chimpanzees - Sana Inoue, Tetsuro Matsuzawa - Current Biology - 2007

- Primate Origins of Human Cognition and Behavior - Tetsuro Matsuzawa - Springer Japan - 2001

- The evolution of the arcuate fasciculus revealed with comparative DTI - James K Rilling, Matthew F Glasser, Todd M Preuss, Xiangyang Ma, Tiejun Zhao, Xiaoping Hu, Timothy E J Behrens - Nature Neuroscience - 2008

- Releasing the Drosophila Hemibrain Connectome — The Largest Synapse-Resolution Map of Brain Connectivity - Michal Januszewski, Viren Jain - Google AI Blog - 2020

- A Connectome of the Adult Drosophila Central Brain - (Many authors) - 2020

- Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems - Raatikainen, Panu - The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - 2018

- Chemically modified guide RNAs enhance CRISPR-Cas genome editing in human primary cells - Ayal Hendel, Rasmus O Bak, Joseph T Clark, Andrew B Kennedy, Daniel E Ryan, Subhadeep Roy, Israel Steinfeld, Benjamin D Lunstad, Robert J Kaiser, Alec B Wilkens, Rosa Bacchetta, Anya Tsalenko, Douglas Dellinger, Laurakay Bruhn, Matthew H Porteus - Nature Biotechnology - 2015

- Biochemistry Online - The Language of DNA - Henry Jakubowski - Biology LibreTexts - 2019